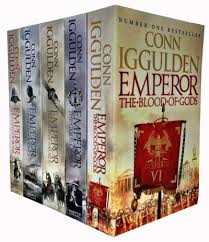

Book Review: Emperor by Conn Iggulden

This five-book series is a great read for lovers of historical fiction. The first four books cover the life of Julius Caesar and the fifth is set in the immediate aftermath of his assassination. The author has taken a few liberties with historical facts and timelines (the inaccuracies are listed in the Author’s Notes at the end of each book) and this review deals only with the story as presented in the books.

Julius Caesar is a complex character to depict and Iggulden does a great job showing us his different facets. We see the young Caesar, full of youthful optimism, ideals and pride in the Roman Republic, rising to power thanks to his boundless energy and personal charisma. He applies his keen intellect with equal ease to war strategy, statecraft and politics, governance and organization, technology and even astronomy, managing to find time between his myriad obligations to reform the Roman calendar with the Julian one. He is driven and ambitious, yet, capable of deep introspection, of rising above the chaos of the moment to be able to comprehend the colossal waste of conflict, whether in his regret at the crucifixion of thousands of rebels all along the via Appia in the brutal aftermath of Spartacus’ slave rebellion or in his sorrow at the destruction of the Library of Alexandria. Yet, his ideals begin to give way to the lure of ever-greater power and each personal victory is marked by a matching rise in ambition. His internal conflict is best illustrated when he pauses on the banks of the Rubicon to weigh his choices. He is not new to war or bloodshed, but in crossing the Rubicon, he knows he will be marching his legions not against an enemy, but against Rome itself. He weighs his personal ambition against the thousands of lives that will inevitably be lost and countless more marred by a bloody civil war, and his decision is a matter of history.

The other superb portrayal in the book is of another equally complex character – Marcus Brutus. Caesar’s childhood friend, he starts out being intensely loyal, on one instance, even giving up command of a legion he has almost single-handedly built to Caesar without a second thought. He unquestioningly supports Caesar in both his political manoeuvring as well as military conquests. There is a degree of expected rivalry between the friends, but all Brutus wants, finally, is to be acknowledged by Caesar as an equal. Caesar, however, is occupied with his own plans and ambitions and fails to see this. For a reader who already knows how this particular friendship will end, there are multiple occasions in the book where you wish you could shake Caesar by the shoulders and tell him to stop taking his friend for granted. And perhaps Caesar does realize it, though belatedly, after Brutus goes over to the side of his rival, Pompey, in the Roman civil war. Because, when Pompey’s forces are defeated, Caesar, in an uncharacteristic move, pardons Brutus and even re-admits him into his inner circle. Ironically, it is this act of kindness, and perhaps of atonement, that seals the fate of their friendship. In public imagination, Brutus goes from being an admired military general to being the man Caesar forgave despite his treachery. His first betrayal, with Pompey, is more a hot-headed, impulsive reaction to Caesar’s favouring Mark Antony over him yet again. After Caesar’s pardon, though, the bitterness and hatred really begins to set in, and from then on, there is almost a sense of inevitability to every step that he takes on the path that ultimately leads to the Ides of March.

There are many interesting women in the story, but the narrative arc and blistering pace of the story sweeps past them all — Cornelia (Caesar’s first wife), Servilia (Brutus’ mother and Caesar’s mistress) and even Cleopatra, leaving us with mere glimpses of their strong personalities. One character I would have liked to have seen and heard more of is Julia, Caesar’s daughter by his first wife Cornelia. Between a mother who dies early and a father who is away on distant conquests for years on end, she has a lonely upbringing, and is married off early to Pompey, consul of Rome and many years her senior. It is a political match, of course, with Caesar trying to protect and consolidate his position in Rome during his lengthy absences, leading conquest in Gaul and beyond. But the political winds turn. Iggulden portrays Julia as being alive and present in Greece during the civil war between her father and her husband (in reality, she is believed to have died before the event), but assigns only a vague and tangential role to her in the scheme of things.

Finally, any story of ancient Rome is incomplete without its legions. War, by its very nature, is chaotic and difficult to pin down in neatly penned paragraphs. But, here is where Iggulden excels. On the one hand, he shows the awe-inspiring discipline of the legions and military precision of everything that governs their lives, right from setting up camps at the end of long marches, legion hierarchies, security precautions, signalling systems, to the mind-boggling minutiae of preparing for battle. At the same time, he manages to precisely convey the chaos of the battlefield –the handful of days, or even hours, when two sides ultimately clash to determine the fate of all the months of preparation and marching. Life is cheap on the battlefield, every erroneous command leading to needless lives lost, commanders have their horses killed under them and are unable to see the action enough from ground level to guide their troops, instructions are lost in the chaos or reach the frontlines too late to make a difference, a few men turning and running at the frontlines spirals into the rout of an entire legion. At one point in Gaul, Caesar retreats in the dark from a legion of his own men, believing them to be the enemy due to a mistake by an inexperienced scout. (I thought this was a fictional element, but turns out from the Author’s Notes, something like this actually happened) Iggulden succeeds in at once giving readers a bird’s eye view of the action as well as plunging them right into the thick of things.

In all, a well-narrated, riveting story with a familiar underlying theme – the one oft-repeated lesson of history that humans, whether as empires, nations or individuals, seem completely incapable of ever learning – how idealism, energy and self-belief are slowly transformed by time and power into greed and arrogance that make them blind to their own fallibility and lead ultimately to their downfall.